Sermons

“THE SPIRITUALITY OF PENTECOST"

5/23/21

The Spirituality of Pentecost

Pastor Noel Anderson, First Presbyterian Church of Upland

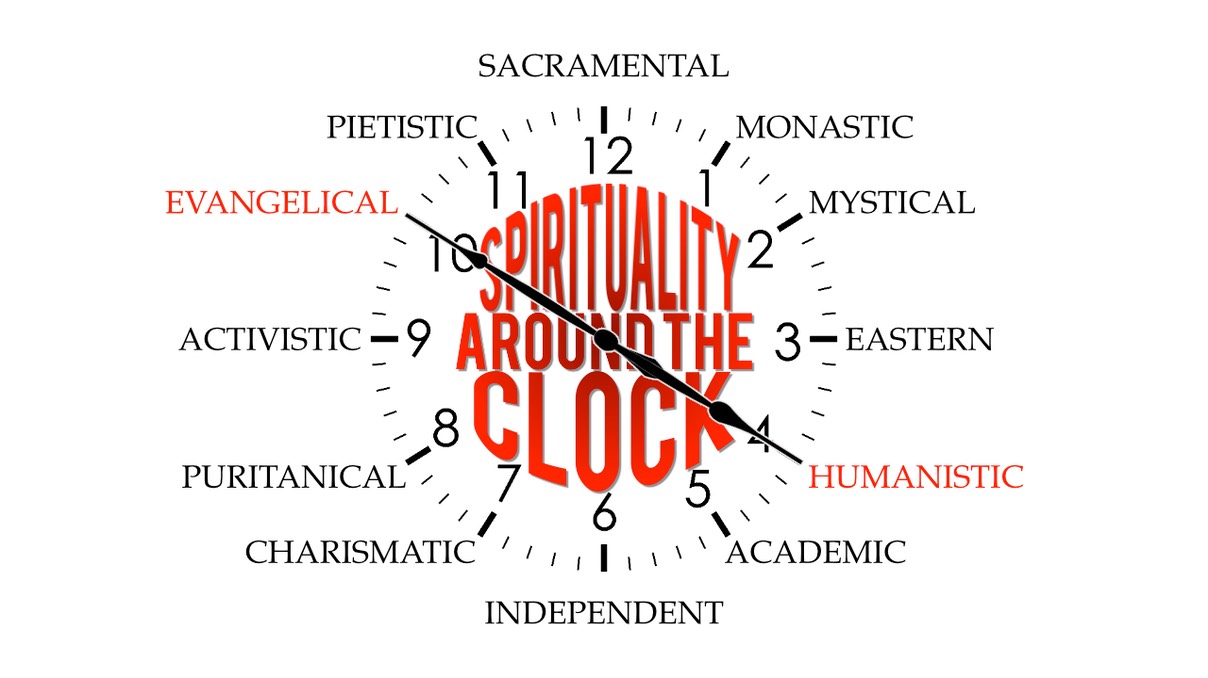

So we have looked at twelve kinds of Christian spirituality since Easter—twelve ways that we can grow into Christ and Christ-likeness. With each one, we’ve seen positive and negative aspects. We see the qualities of Christ and of our Christian heroes as well as the tarnishing of every spirituality by pridefulness. The path of faithful spirituality is indeed a walk along the razor’s edge—a tightrope walk demanding that we keep a careful balance of strengths. But the largest lesson on Christian spirituality comes with Pentecost itself.

There is only one element that can give each of these spiritualities their full value and without which they are all mere vanity. That is the power and presence of the Holy Spirit. Today we look at the difference the Holy Spirit makes, and that Spirit is everything.

Shavuot: Jewish Pentecost

Remember, Pentecost is a Jewish holiday. Pentecost means fifty, and fifty days after Passover is Shavuot. The word “shavuot” means “weeks,” and it is the celebration of the first grain harvest. In the Temple of Jerusalem, the gift of first fruits of the harvest were brought in. Today, Jews celebrate the giving of the Torah—the Law of Moses—and some do all-night readings in celebration.

The Law is celebrated as God’s gift, even though it is the measure by which God’s people fall short. It is the high bar no human being can clear except Christ alone. The Law steered God’s people forward through history, and though they fell, the Law told them how to stand upright again.

For Christians, Pentecost marks the first fruits of the Holy Spirit—the first harvest of Christianity. It is the gift of the Holy Spirit which fulfills the words of the prophet Jeremiah:

But this is the covenant that I will make with the house of Israel after those days, says the Lord: I will put my law within them, and I will write it on their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people. No longer shall they teach one another, or say to each other, “Know the Lord,” for they shall all know me, from the least of them to the greatest, says the Lord; for I will forgive their iniquity, and remember their sin no more. —Jeremiah 31: 33-34

Written on our hearts, the knowledge of the Lord—that is the Holy Spirit given at Pentecost, the first fruits of the fulfillment of the kingdom of God. The Holy Spirit is God’s gift to the Church, and it relegates the Law to the status of babysitter—that which kept us and guided us until Christ should come, send us His Holy Spirit, and dwell among us for our comfort, encouragement, and empowerment. .

The Spiritualities: Potential Idols

We may think of spirituality as a good thing, but I would rather suggest that it is, to an equal degree, potentially evil. Every spirituality can be, like the Law, a source of human vanity.

In Jesus’ ministry, we see him again and again catching friction from the Scribes and Pharisees, who had grown so adept at serving the Law that they failed to serve God who gave them the Law. The Law can become exactly like an idol, taking the service that belongs to God alone. It’s the same way with all the spiritualities.

Let’s consider each without the Holy Spirit and with.

Sacramental spirituality

The sacramental spirituality leans upon the rituals established by Christ. The Church preserves them and passes them down from generation to generation regardless of contemporary thoughts and trends. To share in a sacrament is to immerse oneself in an act of remembrance that precedes us and one that will long survive us. The self is lost in the greater whole of the drama, and we become aware that we are the very temporary players in this drama.

Without the Holy Spirit, we see a very human, cultural preservation society—a group worshiping itself and its own heritage. That is pretty worthless, spiritually speaking, but with the Holy Spirit, the spirituality of the sacraments becomes our foothold in eternity, for in those sacraments—Baptism and The Lord’s Supper—we commune in spirit and in truth with the eternally living God who feeds us, sustains us, heals us, and prepares us for the gift of eternal life.

Independent Spirituality

Independent spirituality puts us in the shoes of Martin Luther who said, “Here I stand!” We trust our conscience to the extent that family, friends, and the riches of the world could not move us or tempt us to sell out. It is conviction that is not in any way associated with “the warmth of the herd” or flock. The independent spirituality reminds us of the prophets who dwelt in the wilderness and remained impervious to peer pressure of any kind.

Without the Holy Spirit, independent spirituality leads to self-absorption and the dangers of isolation. Without the Holy Spirit it is impossible to distinguish the truth from our cherished delusions.

With the Holy Spirit, the practitioner of independent spirituality is never alone. Off in the desert, locked in solitary confinement, excluded from society—he or she has the deep comfort of God’s presence. The Holy Spirit is the independent’s conscience and guide, empowering him or her to stand for Christ whatever may come, even without the blessing of fellowship.

Monastic Spirituality

Monastic spirituality takes to heart Paul’s words to the Romans when he says, “Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewing of your minds, so that you may discern what is the will of God—what is good and acceptable and perfect.” (Romans 12:2). Monastics seek to imitate Christ by embracing poverty, chastity, and obedience to God in all things. It is an immersive lifestyle—one of work, prayer, worship, silence, and contemplation.

Without the Holy Spirit, it is just an exercise in self-denial.

With the Holy Spirit, monastics are indeed transformed, gaining minds that the world will never quite understand. To have a quiet mind is a thing most people in our time can’t imagine, and those who can tend to think it terrifying. But for the monastic, it means peace and a close walk with Christ indeed.

Charismatic Spirituality

Charismatic spirituality rightly engages the senses and emotions in prayer and worship. Charismatics know how to lay bare the psyche before God, holding nothing back in their approach. And they are so right in doing so—we Presbyterians lag far behind in this matter! Their worship is totally demonstrative—every thought, feeling, and intention comes right to the surface and is presented to God in totality.

Without the Holy Spirit, charismatic worship becomes mere sensationalism, or shared sentimentalism—not unlike a headbanger, heavy metal concert. Without the Holy Spirit, it’s just folks working themselves into an emotional lather, a vanity.

But with the Holy Spirit, their every activity is translated into praise and the glorification of God. And as much of themselves as they can bring to the surface and present to God, God touches, heals, transforms, and comforts. We can not heal or change what we do not acknowledge. Reveal little, gain little. Reveal much, benefit much. We all have something to learn from charismatics.

Mystical Spirituality

Mystical spirituality depends upon extraordinary personal experiences—altered consciousness or altered awareness. The extremely subjective experience of God produces visions and insights, many of which encourage the Church.

Without the Holy Spirit, these experience are suspect. Brain chemistry gone awry, such experiences are little more than hallucinations that could have been brought on by LSD or psychoactive mushrooms.

But with the Holy Spirit, these experiences—once shared with the whole community of faith—awaken wonder and new faith. Mystical spirituality can awaken us all into renewed perspectives and transformed minds.

Puritanical Spirituality

In puritanical spirituality, all the things which separate one from total devotion are removed. The puritans were minimalists, dedicating themselves to the core of Christianity. Their devotion and dedication are unparalleled.

Without the Holy Spirit, puritan spirituality is self-righteousness and spiritual superiority. Like the Pharisees, they are the “holy ones” quietly self-congratulating as they condemn the sins of the world.

With the Holy Spirit, puritans can be a powerful witness to the world of changed lives. Such puritan spirituality speaks a loud witness to a world caught up in stuff, things, and social media follows. We could use more puritans today.

Eastern Spirituality

The eastern spirituality similarly shuns the ways of the world to find enlightenment and peace within. Meditation and the cessation of desire are its central practices.

Without the Holy Spirit, it is as best a kind of self-absorption and at worst a form of egocide—the union of the self with nothingness and death. But with the Holy Spirit, eastern practices offer Christians powerful ways to pray. Inner peace, healing, and heartfelt gratitude can replace the anxieties of this world.

Activistic Spirituality

The activistic spirituality is out there, making a real-world difference in the political and economic realms. Community organizing, public protests, marches on Washington, social movements—all serve as ways to serve The Lord and his world.

Without the Holy Spirit, it is all vanity—parades of self-empowerment and collective selfishness. Just a group version of dog-eat-dog king of the hill. But with the Holy Spirit, activism presents a powerful witness to the world that God is caring and active within and among His people for the good of the world.

Humanistic Spirituality

Humanistic spirituality celebrates the goodness of God’s creation of humankind. People are awesome, and there are no limits to what they can achieve when they are positive-minded and put their heads together to make things happen. Science, medicine, space travel—all point to an enormously untapped human potential.

Without the Holy Spirit, humanistic spirituality thinks itself to be God and we have the Tower of Babel—endless ambition leading to chaos and confusion. But with the Holy Spirit, we have a mission and in loving cooperation stretch ourselves to do things previously undreamed of and never thought possible. All glory goes to God, but we are fueled to attempt great things and risk much for the gospel.

Evangelical Spirituality

Evangelical spirituality is that collective drive to bring the good news of Jesus to every nation, tribe, and people group. It is activistic, missional, and devoted to the proclamation of Christ. But without the Holy Spirit, evangelicalism becomes another prideful endeavor, focused more upon the self-gratifications of accomplishment than the glory of God. Sadly, that happens a lot—the world is seen as a pool of hell-bent sinners waiting to be saved by. . . us!

With the Holy Spirit, people truly come to know the grace of Christ and many will follow Him in spirit and truth.

Academic Spirituality

The academic spirituality is central to disciple-making. We all receive instruction, nourishment, and nurture from studying Scripture. We gain insights and wisdom as we do so. But without the Holy Spirit, it is a process of one-ups-manship and arrogance—establishing superiority and knowing-it-all. Knowledge, by itself, puffs up. But with the Holy Spirit, love and devotion to God undergird our learning, so that we move toward greater wisdom, and we experience study—and teaching—as a deep joy.

Pietistic Spirituality

Pietistic spirituality seeks utter devotion to God, giving ourselves—our hearts, mind, and souls—in totality to the Lord. There is nothing the pietist wants to keep to him or herself. It is all about God and all about the goodness of God.

But without the Holy Spirit, it is vanity. Piety becomes the new rule—the new Law—and pietists part of a club whose code they are most dedicated to enforce.

With the Holy Spirit, pietistic spirituality knows that all good is a matter of God’s grace alone, and pietists rest in the joy of God’s perfect love and providence. Only by the Holy Spirit can we love God. And with the Holy Spirit we can and do.

The Spirituality of Pentecost

The gift of the Holy Spirit is the great center—the source that gives all spiritualities their authenticity and power. With the Holy Spirit, all spiritual disciplines and styles have strength and value. Without the Holy Spirit, they are all vanities—pointless observances devoid of direction and value.

We at First Pres are utterly dependent upon the Holy Spirit to make good of anything we would attempt. Any spirituality, any thought, study, activity, or mission—all depend on the Holy Spirit’s initiative and encouragement.

Without the Holy Spirit, this is all a total waste of time and effort, but with the Holy Spirit, we live the abundant life to God’s glory.

Pentecost is God’s gift to the Church and to you and me individually. Because of that Spirit, our entire life can be transformed into worship. I’ve named twelve spiritualities, but there may be twelve-thousand! We can practice our spirituality and know the presence of God in every moment of every day. There is nothing that is outside of spirituality because our relationship with God is constant!

As we move forward into the new, post-covid climate of 2021 and beyond, let us be thoroughly, deeply mindful that the Holy Spirit is with us and among us, ready to transform any moment of the day into an experience of God’s power and presence.

†

Following Up:

- How is it that service to The Law can become like idolatry?

- How can spirituality in general turn into a kind of idolatry?

- Review each of the 12 spiritualities. Consider for yourself:

- Which come naturally to you?

- Which are most unlike you?

- Which are most familiar—most common among most Christians you know?

- Which seem the strangest?

- Do some seem to be more risky or potentially dangerous?

- Which have you never considered as spirituality—or at least not as “Christian”?

- Are there any among these that piques new interest for you

- Consider “stretching yourself” and developing one or more of the spiritualities for which you have your “lowest score.” If you are in a group, name your challenge and keep each other accountable for exploring what is new.

- What is the one factor that separates all spirituality from vanity and idolatry?

- Consider how other Christians may have other basic spiritualities than you, and how that knowledge can become a strategy for your relationships.

- What are ways we can affirm others with very different spiritualities than the ones we prefer?

- How many different spiritualities is it possible to live-out in a single day?

Spirituality Around the Clock: “ACADEMIC/PIETISTIC"

Sermon 2120

Academic/Pietistic

Pastor Noel Anderson, First Presbyterian Church of Upland

Today we are at 5 and 11 on the clock—Academic spirituality and Pietistic spirituality. These two stand in the balance as differing forms of righteousness based on discipline. Both tend toward competitiveness, and both run the risk of Pharisaism. The human propensity toward pride and pomposity seems to be boundless, and we'll see how it can turn two good spiritualities bad, even as we celebrate the good in each.

Academic Spirituality

In the the Great Commission, the key verb rendered “making disciples,” means instruction. The key business of disciple-making is not a dozen different kinds of spiritual formation activities; it is instruction, book learning.

In the Jewish world, the study of Torah is central. In Jerusalem, near the Western Wall, there is a yeshiva where orthodox Jews study all day long. They memorize Scripture and the Talmud (Mishnah and Gemara). One man there shared with me a source of their intensity. He said, "When Messiah comes, will he find understanding? We are obliged to know the Law and meditate upon it."

Our text from Deuteronomy is the "Shema"—the essential prayer in Israel and still the basis of Jewish piety. Notice how much of it looks like study—hear, keep, recite, bind, fix, write—the basis of academic spirituality.

Jews and Christians have been called "people of the book" because our faith, unlike that of any other religion, is grounded in Scripture—particularly God's self-revelation proclaimed in writing.

Academic spirituality lives in the head, where understanding, wisdom, and intelligibility live. Fides Quarens Intellectum—faith seeks understanding, was given by Augustine and Anselm to remind the Church that when faith is authentic, it remains hungry to learn more.

We experience academic spirituality whenever we hunger for insight and new understanding. Our faith grows in studying Scripture. Who among us has not had the experience of reading a text or hearing it explained and had that marvelous "Aha!" of illumination? The lights go on, and we feel like we're looking at the world in a new way. Or we read a commentary that hits us just right, and we feel we have a better grip on the faith and a deeper understanding.

Academic spirituality can be transformational. How many stories have we heard about atheists reading Scripture to find ammunition against Christianity only to find themselves troubled into belief? How many thousands of anecdotes are there of someone's faith left hanging by a shred when they turned to the Bible for encouragement only to find they fell onto precisely what they needed to hear to deepen their faith?

In Christianity, academic spirituality has found its most significant development in theology. Theology is not merely a study but a unique activity of the Christian community. We approach Scripture prayerfully, yes, but also philosophically—with analysis, synthesis, and education. Christianity is the only "religion" to create its own skepticism. From the beginning, we have not only introduced a rigorous critique of our own ideas, thoughts, beliefs, and interpretations, but we have promoted and endorsed this self-criticism. Most religions work to build themselves up. From the beginning, Christianity thoughtfully seeks to keep itself lean, sloughing off heresies and personal elaborations in every century. Sorting out the chaff is a matter, not so much of heart but of the head. A correct knowledge of Scripture and the Apostles' faith is necessary for steering the Church through the rapids of human history.

WHERE ACADEMIC SPIRITUALITY GOES WRONG

Three things send academic spirituality sideways: pridefulness, isolation, and neglecting the heart. We know that spirituality which lives only in the head will soon prove inadequate. We know that the Ivory Tower can alienate people from relevance and that some people can be educated beyond their intelligence, proving themselves little use to the Church or the work of the kingdom.

The biblical model for academic spirituality would be the Scribes—the academics of the Temple—and they are usually spoken of as villains in the gospels. They were the intelligencia of their day, the professors and doctoral students deeply committed to knowing Scripture and the commentaries. We also know that academia—be it in the Jerusalem Temple or today's universities—tends toward competitiveness. King of the hill, dog-eat-dog, insiders, and outsiders is a hierarchy of accomplishment and competence. Hence, academic spirituality can become fiercely Pharisaical—holier than thou, pompous, superior, rigid, and inflexible. For all their pretended liberality, many universities resemble nothing so much as Medieval Catholicism—power-hungry and reserving to themselves the right to be the ones who may bless whatever else goes on in society.

In my experience, I have witnessed more pompous self-importance among certain college professors than I have seen anywhere except at Presbyterian General Assembly meetings. When academic spirituality is infected by pridefulness, it changes lovers of learning into lovers of self-importance.

To than unfortunate distortion, Jesus says in Matthew 23: 13:

"Woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For you lock people out of the kingdom of heaven. For you do not go in yourselves, and when others are going in, you stop them."

Clearly, intelligence is not everything.

It is possible to have eyes yet not see and ears yet not hear. Without the essential ingredient of faith, any study can default to the blind leading the blind.

ACADEMIC SPIRITUALITY IN JESUS

Do we see the academic spirituality in Jesus? Yes. At 12, he was in the Temple, astounding the rabbis with his insights. That Jesus even bothered to sit in with them and ask questions or be questioned exhibits the academic spirituality. At its best, academic spirituality is communal, which only happens when shared by several people rather than in isolation.

Elsewhere, it isn't easy to find because Jesus did not need to be taught or learn from any human being. His knowledge and insight were divine and direct from the Holy Spirit.

For us as well, our best academic spirituality involves our humble submission before the Holy Spirit, asking and trusting the Spirit to teach us and guide us into all truth. It is right and good that we should be constant students ever-eager to have our faith more fully and completely informed by Scripture.

We practice academic spirituality when we:

- discipline ourselves in the study of God's Word.

- discipline ourselves in the study of God's world.

- seek the joy of learning and teaching.

There is a clear difference between talking about God and talking to Him. There is no way to grow in faith or rightly learn things of the faith without first couching our study in prayer and faithful submission to God's Word. And there are great rewards—great joy and growth—in the discoveries that come with the Spirit's teaching.

PIETISTIC SPIRITUALITY

Whereas academic spirituality concerns the head, pietistic spirituality concerns the heart. The keyword is devotion. The same text that serves for the academic spirituality can do for the pietistic spirituality as well:

Deut. 6:5: You shall love the LORD your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your might.

It is the first and greatest commandment. It is also the heart of pietistic spirituality, getting the whole heart, soul, mind, and strength into the business of loving God.

In the West, pietistic spirituality received a major kick-start from John and Charles Wesley, George Whitfield, and others who would spark evangelical revival in England and the United States. And it is here pietistic spirituality overlaps with evangelical spirituality, for here was the first time the word evangelical was applied to a person as a specific Christian identity.

A good picture of pietistic spirituality comes from the "Holy Club" of Oxford—of which the Wesleys and Whitefield were leaders.

THE HOLY CLUB

The name Holy Club was given to the group in mockery of their emphasis on devotions. It was the first sign of what later became Methodism. Begun by the Wesleys at Oxford in 1729, the Holy Club members fasted until 3 PM on Wednesdays and Fridays, received Holy Communion once each week, studied and discussed the Greek New Testament and the Classics each evening in a member's room, visited prisoners and the sick, and systematically brought all their lives under strict review. It is this systematic review that became their "method." "Methodism" was also a name given in derision by other thinkers at Oxford.

The "method" consisted of 22 questions:

1. Am I consciously or unconsciously creating the impression that I am better than I really am? In other words, am I a hypocrite?

2. Am I honest in all my acts and words, or do I exaggerate?

3. Do I confidentially pass on to others what has been said to me in confidence?

4. Can I be trusted?

5. Am I a slave to dress, friends, work, or habits?

6. Am I self-conscious, self-pitying, or self-justifying?

7. Did the Bible live in me today?

8. Do I give the Bible time to speak to me every day?

9. Am I enjoying prayer?

10. When did I last speak to someone else of my faith?

11. Do I pray about the money I spend?

12. Do I get to bed on time and get up on time?

13. Do I disobey God in anything?

14. Do I insist upon doing something about which my conscience is uneasy?

15. Am I defeated in any part of my life?

16. Am I jealous, impure, critical, irritable, touchy, or distrustful?

17. How do I spend my spare time?

18. Am I proud?

19. Do I thank God that I am not as other people, especially as the Pharisees who despised the Publican?

20. Is there anyone whom I fear, dislike, disown, criticize, hold a resentment toward, or disregard? If so, what am I doing about it?

21. Do I grumble or complain constantly?

22. Is Christ real to me?

WHERE PIETISM GOES WRONG

Pietism can go wrong very quickly, turning a person from the humble Publican into the sanctimonious Pharisee. It happens in three ways:

- when it goes PUBLIC.

- when it becomes PROUD.

- when it becomes a CODE.

These are all deadly and among the worst stains on Christianity and the Church.

In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus spells it out:

"Beware of practicing your piety before others in order to be seen by them; for then you have no reward from your Father in heaven." Matthew 6:1

When pietism goes public, it goes bad. Jesus makes it clear that our piety and good works are meant for God's eyes alone. That becomes difficult—perhaps impossible—if you create a Holy Club and a piety code.

Also, once piety is practiced, we start to notice how well we practice it and how poorly some of our brothers and sisters practice it. It isn't long before the number one deadly sin creeps in, and we are secretly praying: "Lord, thank you for helping me live above the norm. I fast twice a week, I tithe, I pray three times a day,”etc.

It is no wonder the world perceives Christian devotion as self-serving and sanctimonious. Self-righteousness is perhaps the most significant open wound of our Christian witness. Pride ruins every good thing it touches.

Thirdly, once piety becomes our mutual agreement (of which we are very proud), it becomes a new code. "We Methodists/Presbyterians/Catholics shall covenant together to live by a certain rule by which we shall more completely honor God." Good intentions, yes, but the path the Hell nonetheless. Our little codes are our idolatries, and they are practically impossible to escape.

Every worldly institution—every denomination—has its rule, its order, its code. Those codes may be well-intentioned to help us collectively better follow Jesus, but we inevitably come to serve the code rather than Jesus Himself. I hardly need to point a finger elsewhere because we Presbyterians are as bad as any.

"That's not the Presbyterian way!" I have said many, many times.

"It's not in the Book of Order!" Again, I have played my role as enforcer of the denominational code, again and again. It is part of my Pharisaism, but I take no pride in it. I endure it as a necessary evil in the world of fallen people and even more fallen institutions.

Where do we see pietistic spirituality done rightly? With Christ, of course.

Jesus devoted himself in prayer, usually off by himself, Scripture records. He fasted 40 days and fought temptation in the wilderness. He washes the Disciples' feet, demanding that they allow Him to serve them. Beyond these, only one image matters: the cross. It is the perfect picture of love, devotion, and commitment to God.

Our pietism is rightly not our own at all. We do not—and we must not depend—upon our own attempts to reach up and get right with God. We must resist the temptation to put our hands on the wheel and steer our well-intentioned course of righteousness. This is Christian idolatry. We should rather empty ourselves of ourselves and depend entirely on Christ's piety which works on our behalf. It's not about us; it's not up to us. It's all about Christ; it's all about Him.

We can and should practice pietistic spirituality. We do so whenever we:

- empty ourselves before Christ.

- seek greater commitment in following Him.

- devote our entire heart and life to Him.

Finally, just a note about each. As regards academic spirituality, we know that knowledge puffs up, but love builds up. Love can correct our academic trajectory better than anything else. The love of God and our neighbors is the most excellent foundation for our studies.

And I didn't even mention the very best part of pietistic spirituality, which is music. The Wesleys wrote many hymns. They were singers and put their whole hearts into worship. Music in worship is God's gift to the human heart, and it is there to soften us up enough that we might further humble ourselves and receive the Word of God.

Lastly, the best examples of pietistic spirituality done right that you and I will see with our own two eyes lives in many of our homes and walks on four legs (Sorry, cat owners; I'm talking about our dogs. Yeah, we have a cat, but they're no match for the devotion of a dog). When I'm at home, and my dog is on my lap looking up into my eyes thinking that I am the greatest thing in the cosmos, I believe that is how I should be devoted to God—endlessly and without limits. It’s funny and oddly just that our endeavor to become more Christlike should begin by taking lessons from our dogs, but that’s how it works: the way up is the way down, and the path to life is the cross of death.

†

Following Up:

- Read through the 22 questions of The Holy Club and either share or journal how you “measure up” in pietistic spirituality.

- Commit yourself here and now to reading something excellent to grow your understanding of the faith.

Among recommendations: - Anything by C.S. Lewis.

- Anything by Frederick Buechner.

- Life Together by Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

- Letters from Prison by Dietrich Bonhoeffer.

- The Cure by Lynch, McNicol, and Thrall.

- Anything by N.T. Wright.

- Anything by Henri Nouwen.

- Any Church history subject.

- Knowing God by J.I. Packer.

- Confronting Christianity by Rebecca McLaughlin.

- Orthodoxy by G.K. Chesterton.

- The Confessions of St. Augustine.

Your Pastor is always willing to recommend more!

Spirituality Around the Clock: “HUMANISTIC/EVANGELICAL"

Humanistic/Evangelical

Pastor Noel Anderson, First Presbyterian Church of Upland 5/9/21

Humanistic Spirituality

There is the humanism of the renaissance and the humanism of our time—from the 18th century forward—and the two should not be confused. The first was a re-embracing of classical literature and philosophy, the latter a result of science and modern philosophies. We’ve become familiar with the term “secular humanism,” which is the result of humanism once it disregards God entirely, but our interest is in Christian humanism, which is a Christian spirituality grounded in Scripture and the life of Christ.

In a nutshell, humanism holds that “Man is the measure of all things.” The good of humankind is the sole barometer of our morality, faith, and practice. Ethics or theology which do not result in worldly good are seen as completely irrelevant.

In theological circles, the buzz-phrase has become “human flourishing.” Human flourishing becomes the chief factor by which the church and its theologies judged. If something seems good in promoting human flourishing, it is a good thing. If it bears no weight in the human sphere, it is irrelevant—even bad.

We see the humanistic spirituality in Christ as well. When the great multitude gathered on the grass by the lake [Matthew 14], the Disciples worried for their worldly care. “Send the crowds away so they can find some food.” But Jesus says, “YOU feed them.” Though they were poorly resourced, Jesus took what they had and miraculously fed the multitude. At one level, this is Jesus caring for the simplest of human needs—their hunger. He also heals the sick, casts out demons, and in other ways sets aright many of the worldly manifestations of inequality, inequity, decay, and death—all results of human sinfulness.

Humanistic spirituality maintains a laser beam, horizontal focus on the world. It tends to rely on the goodness of the image of God found in every person. Yes, we’ve sullied it, but it remains there waiting for good people to awaken it, encourage it, and groom it into full flourishing.

It believes in collective good. If people will set aside their differences and look to the concerns of all instead of self alone, then there is no end to what we may accomplish.

The song “Imagine” by John Lennon provides a poetic description of this vision. “I hope some day you’ll join us and the world can live as one.” Christian humanism graciously looks the other way over the “above us only sky” lines, though it expresses their value regarding human flourishing.

The goal is peace, a good and Godly aim.

You and I practice humanistic spirituality whenever we:

1. help others to pursue their full potential. Humanism believes in that inherent goodness God has created us to pursue.

2. coach, counsel, parent, and teach. I’ve had strict coaches in the past. I feared them, but they knew my potential better than I did. They pushed, challenged, and prodded me—which I hated—but did so in order that I may overcome personal limitations. For their work, I became a better basketball player, a more diligent student, and a more confident man. I remain deeply grateful to them all.

3. practice activism. Here humanistic and activistic spirituality overlap. In becoming active—even politically active—we seek justice, peace, and equity for all people in a way that can bear fruit and diminish human suffering. Despite the excesses of many kinds of activism—only too much in evidence today—there is at the core of any activist the desire to help improve someone else’s station in life or to otherwise enhance human flourishing. We may disagree on the means and methods of affecting such change, but Christians should all be in agreement that human suffering merits a helpful response from the church.

Where Humanistic Spirituality Goes Wrong

Humanism goes wrong precisely to the degree humankind is elevated to the place of God and God’s being and relevance is commensurately minimized. What happens to our ideas about God when humankind and its needs are placed at the center of the universe? It’s obvious: God becomes less than God—a distant observer or an otherwise irrelevant aspect of human thought and behavior.

The problem with humanism in general is that it fails to provide anything greater than humanity itself. Faith and belief are only relevant to the degree they assist the first cause of human flourishing.

Some years ago at a World Council of Churches meeting, a banner hung across the back of the stage:

“GOD IS OTHER PEOPLE.”

It is Matthew 25—“what you do for the least of these you’ve done for me”—on steroids. God’s spirit is imminently present within every person, so our service to Christ depends upon our service to humankind, right? What is “faith” but doing what is good for other people? So say some.

The failure of humanism—and the humanistic spirituality—is found as far back as Genesis 11 in the Tower of Babel story. The seeds of humanism flourished among those who decided it was time for humankind to build its way into the place of divinity.

“Come, let us make a name for ourselves,” they said, implying that they, too, could—with all their collective virtue—share a place with the gods in heaven. The ultimate end of this ambition was—and is—utter chaos.

Evangelicals / Evangelicalism

The word evangelical has become so problematic that in 2008, a group of Evangelical theologians produced a document called “An Evangelical Manifesto.” The purpose of this document was to address the less-than-well-informed media, which had collectively besmirched the term through increasing misuse. There are still many wrong ideas about evangelicals.

The word means “good news.” The original use of the word “evangelist” had nothing to do with Christianity. It was a Roman term. The role of an evangelist was to travel town to town in the ancient empire and announce the good news of one-Caesar-or-another’s military victories. This was news in antiquity. Yes, we Christianized it, so the word evangelist rightly refers to one who travels town to town announcing the good news of Christ’s utter triumph over sin, death, and Hell.

Since the Reformation, the world evangelical has served as the preferred synonym for “Protestant,” as the word protestant was originally derogatory—used by the Roman Catholic writers against the Reformers. Early Protestants never called themselves Protestants; they called themselves Evangelicals.

In truth, evangelicalism is diverse and broad. There is no particular political allegiance rightly associated with the word. We can say that it is every bit as diverse as the word Protestant.

What Evangelicals hold in common includes their reliance on the authority of Scripture, and their close alliance with the Great Commission—to make Disciples of all nations. Evangelicals take the Great Commission most seriously.

Evangelical Spirituality

Evangelical spirituality, while sharing a great deal of horizontal focus with Humanistic Spirituality, operates with different values and ends.

Unlike the humanists, who say man is the measure of all things, Evangelicals hold that God is the measure of all things. God is above all, over all, and even Lord of those who deny Him. As ChristianHumanists have said, “God is other people,” Evangelicals add an all-important comma to the phrase:

“GOD IS OTHER, PEOPLE.”

For Evangelicals, human flourishing is not the most relevant measure, but rather God’s glory. The glorification of God is infinitely more important than human flourishing. In a choice between God being glorified and humankind being happy, God’s glory comes first.

If God’s glory were served by the end of all life on Earth, then that would be the higher good. Should God’s glory be served by there being no cosmos instead of one, then that is the higher good. We can be thankful that God is indeed glorified in human flourishing, but it isn’t necessarily so. When humanity lives in peace and wholeness, The Lord is glorified because we approximate his will and design.

Assisting human flourishing is a worthy piece of our witness. It is part of seeking justice and faithful stewardship of God’s creation, but to be clear, human flourishing is no end in and of itself.

The humanist side of evangelicalism is outreach. The Evangelical’s chief concern for humankind is in the knowledge that every human being is more than a mere animal, but rather a soul on a trajectory either toward or away from God. Once this biological life is ended, the soul remains accountable to God. Evangelicals are concerned for more than a person’s temporary well-being; Evangelicals put first priority on each person’s eternal destiny. That is human flourishing indeed.

At its best, Evangelical Spirituality remains intent upon the mission of the Church as given by Christ. We glorify God when we obey his commands: to love God, love neighbor, and make disciples of every people group in the world.

Where Evangelical Spirituality Goes Wrong

Evangelical Spirituality can go wrong in several ways. It can become an exclusive club, a collection of insiders celebrating their own, Evangelical identity. This is self-serving and is reflected when their collective interests become ingrown, “about us Evangelicals” in spirit.

When Evangelicalism focuses on its “ism” rather than its charge to serve, it abandons its charge to serve and can become a community in worship of itself, just as with any common religion or identity movement.

It also goes off when it becomes privatized—when being an Evangelical is something that lives only between one’s own ears. God has created this world as the theater for our spiritual development. We are meant to engage the world, not to climb into a bubble and avoid it.

You and I practice Evangelical Spirituality whenever we:

1. serve Christ’s glory, will, and purposes. To love and value God above all else—the world and collective humankind—is the earmark of evangelicalism.

2. pursue mission, evangelism, education, and nurture. Like the humanists, Evangelicals devote themselves to the encouragement of all that they may develop their God-given gifts and share in the ongoing mission of Christ. The goal is growth, both internal growth and depth of the faith as well as growth in fellowship through outreach.

3. serve God’s will, not human comforts. Human flourishing is the cart to be kept well-behind the horse. We are not here for our own gain and comfort, but as servants of God tending to his creation.

As we read in our text from Ephesians:

10 For we are what he has made us, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand to be our way of life.

Christlikeness is Our Calling

We see Christlikeness in both Humanistic and Evangelical spiritualities. There are areas they overlap, areas they differ, and areas where they mutually exclude one another.

It is right and good that we should acknowledge the best in every form of spirituality, find a way to embrace it and grow into it, and by doing so grow a little more into the image and likeness of our Lord and Savior Jesus. That is our mission statement here at First Pres. We are growing in Christ—that is, growing into Christ—and making him known. †

Following Up:

- What are the core values of Humanistic Spirituality? What are the signs of success?

- Where does Christian Humanism depart from worldly humanism?

- How do we see the humanistic spirituality exemplified by Christ? Where do we hear him charge us to such spirituality?

- How and where does humanism go wrong?

- Consider sharing personally how you might challenge yourself and grow in your humanistic spirituality.

- What has gone wrong with the word evangelical? How is it rightly understood?

- What is the foundation for Evangelical outreach? Why do we do it?

- How do the ideas about God differ between these two spiritualities?

- Where is the common ground between them?

- Where does evangelicalism go wrong?

- What is the danger of any group celebrating its own identity?

- Consider sharing personally how you might challenge yourself and grow in your Evangelical spirituality.

Spirituality Around the Clock: “EASTERN/ACTIVISTIC"

Eastern/Activistic

Pastor Noel Anderson, First Presbyterian Church of Upland

BE STILL

No spirituality is more intensely inward than Eastern spirituality, and none is so outwardly-focused as is Activistic spirituality. They contrast not only in focus—inward/outward—but also by the role of the ego. In Eastern spirituality, the ego is to be reduced—even eliminated—but Activistic spirituality requires passion, and therefore strong egos.

Eastern spirituality is introspective and ascetic, shunning the ways and things of the world. When Jesus says, “consider the lilies” and “do not worry about what you will eat or wear,” he points us toward a holy kind of detachment. Holy detachment is the practice of separating our hearts from the things of this world—material goods, worries, fears, anxieties, lusts, and envies—so that we would find our good in God alone.

The process for divesting oneself from this world is meditation—for the Christian, it is prayer.

“Be still, and know that I am God,” says the Psalm. Quiet yourself. Remove yourself from the noise and anxiety that makes up this world. Here we have some overlap with monasticism, for sure, but Eastern spirituality is distinguished by its ultimate aims, the cessation of desire, and the destruction of the ego.

THE PROBLEM OF EGO

Eastern spirituality sees the ego as a problem, and who can say it isn’t? Isn’t the ego the source of the majority of sin? Obviously yes. According to the leaders in Eastern spirituality—which can be found in the Greek philosophers every bit as much as in Buddha—the path is to eliminate desire, because desire makes the ego miserable. Meditation trains one in the cessation of desire. [Buddha quote]

Eliminate all the desires of your heart and you become free from suffering. Try this on your favorite teenager sometime. “You’re suffering because you can’t have the new iPhone 13? Well, eliminate that desire and think of how happy you’ll be!”

Christians can benefit from meditation—especially that kind of meditation that leads to holy abandonment. We should seek our soul’s satisfaction no place other than in Christ. It is right and good that we should prune off the attachments to possession and anxious desires that drive us so much of the time.

The ego wants what it wants. Christians should be able to think and act beyond the hungers and gratifications of the ego.

EGO ANNIHILATION

Eastern spirituality, in its most serious incarnations, goes further than that. It’s not enough to merely tame one’s ego, but the ego must be destroyed, annihilated.

The total cessation of desire leaves one empty, and that emptiness or nothingness is seen as a high good with which the enlightened soul must become one.

As one Maharishi puts it:

The more you prune a plant, the more it grows. So too, the more you seek to annihilate the ego, the more it will increase. You should seek the root of the ego and destroy it.

This is ego-cide—the destruction of the ego. We hear something similar in the New Testament about baptism, in which we die to the self and rise to Christ. Our text from Ephesians says it: we are to put aside the old self—being crucified with Christ, we put the self to death.

But Christianity does not end it there. We don’t believe in the destruction of the ego but rather the baptism of the ego. In Christianity, the ego dies to self-service so that it can rise to the service of Christ. The baptized ego is good and blessed, not a problem to be solved.

ACTIVISM

Whereas the Eastern spirituality focuses on the cessation of desire and minimization of the ego, activism is built on passion—strong egos boldly willing to take a stand for what matters.

The problem with Christians too-heavily steeped in eastern spirituality is that they don’t get much done. Now I’m thinking of pastors, here, but it’s a luxury to be able to sit and stare out of the window all day like a spayed cat, and it may make one centered and even enlightened, but where then is the mission?

The Apostle Paul is about as non-eastern and activistic as one can get. He was a head-strong workaholic. He knew what had to be done and didn’t easily compromise with other colleagues, including Peter and James—who were part of Jesus’ inner circle and who led the Jerusalem church.

Without some degree of ego strength, there is no passion. Without passion, things do not get done. Paul had bridges to build, congregations to plant, and clear plans to execute for the spread of the gospel. Paul only relaxed when imprisoned.

I can imagine one of Paul’s brothers saying to him, “Brother, take a break! Go on a retreat, have a sabbatical—spend time in quiet prayer and reflection—you need to this; we all do.” And I can imagine Paul’s reply: “Sure, I’ll meditate—next time I’m thrown into jail—in the meantime, and I say this with love, either help me get on with this mission or go meditate someplace by yourself.”

Activism, at its best, is positive and goal-oriented. At its worst, it is mob behavior. And the thing that turns activism from positive to negative is sin—usually pride or greed—or both.

At its best, activism is virtuous both in its goals and execution of its program. Both Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr were practitioners of passive resistance, which is peaceable non-compliance as a form of protest. It is nonviolent and noble.

In King’s case, passive resistance reveals its spirituality, for it is decidedly Christian in character. The path of the cross is to bear violence, not produce violence or encourage it. The cross was terribly violent, but Jesus absorbed the blows; he did not act in violence, nor did he allow his disciples to do so.

Christian activism will always bear the marks of Christ: peace, patience, kindness, gentleness, and love. Similarly, demonic activism can be known by its fruits as well.

PRIDE RUINS EVERYTHING

The problem, of course, is sin. In time, most good movements get ruined by it. In the beginning, every movement believes its own application of justice is the correct one. “We have the solution” is the common core of its followers. It is also the beginning of the end.

With confidence and conviction, a movement develops a kind of collective egotism. Pride and identity become central, even to the point that the original goals are forgotten, and the movement becomes nothing more than a celebration of itself. It begins with pride and pridefulness and then goes on to greed (which, in the eyes of the activists, is justified), and from there, it becomes willing to wage war. The arguments are oversimplified, the opposition is demonized, and dialogue becomes impossible. This is the shadow side of activism, and Christians need to be salt and light within any movement so that these things do not take over.

As Yoda says in Star Wars, “Fear is the path to the dark side. Fear leads to anger, anger leads to hate, and hate leads to suffering.”Yoda brings wisdom from eastern spirituality to the heroic activist Luke Skywalker in another clip. [Clip]

Luke: “But how am I to know the good side from the bad?”

Yoda: “You will know when you are calm, at peace—passive.”

Calm? At peace? Passive? Aren’t these opposite to activism? Is this how we train soldiers? No, but they do point us to activism of the right kind. Faithful activism is not necessarily social justice, but it is biblical justice, and there are times when these do overlap.

BIBLICAL JUSTICE

Biblical justice speaks for the voiceless, as we read in Proverbs 31. In Scripture, the common idiom for the poor and the oppressed is “the widow and the orphan.” Widows and orphans in ancient Palestine were those with no visible means of support.

Their only hope is in the supply God has given to others. The Bible is clear: God expects us to bless and care for the poor. If I have two meals and you have none, God expects me to share one with you. If you have two meals and I have none, God will not justify your keeping both to yourself, nor will he justify my forcibly taking one away from you.

Biblical justice grows from peace—God’s shalom—and where there is no peace, there will be no justice.

EASTERN/ACTIVIST TABLE

Finally, as we approach the table of Christ, we acknowledge that in Jesus we see the best of all spiritualities. In Christ they come together into a single heart.

Andrew Harvey is a Buddhist Brit living in Chicago who writes about what he calls, “Sacred Activism.” Specifically, “Sacred Activism is the fusion of the mystic’s passion for God with the activist’s passion for justice, creating a third fire, which is the burning sacred heart that longs to help, preserve, and nurture every living thing.”

As we come to the table we practice Eastern spirituality through holy abandonment. We detach ourselves from every other table that would feed us, and from all the noise of the world which would try to tell us who we are what we are worth. We come to the table remembering that in baptism we have died to the self to be made one with Christ.

This table is activism as well, for in taking the bread and cup we identify ourselves with the Jesus movement—a most radical and even violent revolution in which Jesus took the hatred of the world upon himself. He took on all the fear, phobia, violence, and injustice into his own flesh. As we eat and drink, we stand up as activists in that same ongoing revolution. We are fed for our participation in biblical justice and the irrepressible proclamation of the good news of God’s love in the person of Jesus Christ. †

Following Up:

- Western culture is steeped in noise and chattering distractions. TRY THIS: Set aside 30-40 minutes each day for a period of time—a week or a month—and commit yourself to silence. That means no reading, no headphones, no journaling—just silent meditation. It’s impossible not to pray.

- Eastern Spirituality removes us from the noise and distractions, which we need to do so that we don’t confuse ourselves with the noise. “Centering prayer” is a kind of meditation whereby we detach ourselves from the stuff, the things, the obligations, and the anxieties that make up any day. It is here we find peace, gentleness, and the calm responses that are superior to our natural reactions. Such prayer enables us to live deliberately and with self-control.

- Christian Activism issues from peace, patience, gentleness, kindness, faith, hope, and love. Re-imagine every kind of activism we see in the world re-framed by these qualities.

- How is ego a curse? For what is it necessary? How is a Christian to regard the ego?

- The sin of sloth is the refusal to participate—being a spectator when you should be an active helper. Can you think of times you have hesitated to act or neglected opportunities to make a difference in helping others?

- Activism is a response to God’s grace in Jesus Christ. Can you articulate that connection from Christ to acts of biblical justice?

- Where does Biblical Justice intersect with popular, “social justice”? Where and how does it differ and depart?

- How can pride ruin any decent movement toward justice?

- When we’re not sure whether or not we’re doing the right thing, what resources can direct our hearts and minds?

- Confidence and conviction can be expressed through either peace or aggression. How does a calm and peaceable confidence look different from an aggressive one. Which emotions dominate in each case?

- Many activists have come to justify violence in support of their movement. History is chock-full of leaders doing so. Are there conceivable times when Christians should legitimize violent action?

- The cross of Christ was a bloody and violent revolution that changed the world. How does Christ’s “violence” differ from that of most revolutionaries?

- How ought Christians to adapt Christ’s path and pattern in their activism?